The Origin of Matcha and Its Introduction to Japan

Origin of Powdered Tea from China

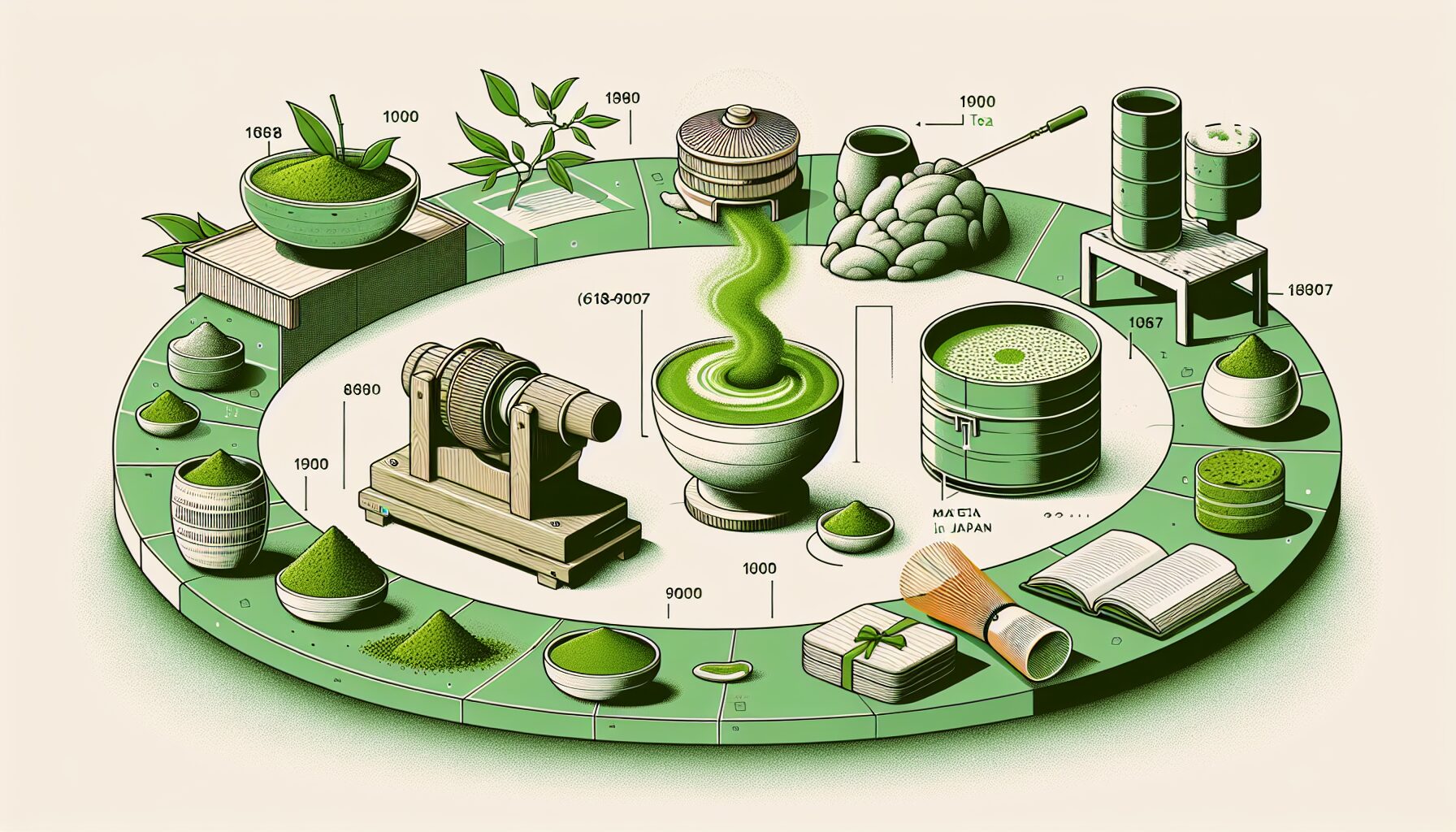

The origin of matcha surprisingly dates back to the Tang Dynasty of China (618-907). At that time, a method called “tencha-ho” was born, where “cake tea” (steamed and compressed tea leaves) was crushed into powder and dissolved in hot water. This is considered the prototype of today’s matcha. In China, it was called “matcha” and spread among the imperial court, nobility, and Zen temples. Particularly during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the tencha-ho method developed greatly, and tea culture experienced a golden age.

Introduction to Japan and Eisai’s Contributions

Matcha was introduced to Japan at the end of the 12th century, during the early Kamakura period. Zen Master Eisai (1141-1215), known as the founder of the Rinzai sect, brought back tea seeds when returning from Song China and authored “Kissa Yojoki,” Japan’s first book on tea. In this book, Eisai wrote, “Tea is the elixir of health and the art of longevity,” explaining the benefits of tea. This triggered the spread of tea cultivation and consumption, primarily centered around Zen temples.

Japan’s Unique Development and the Birth of Tea Ceremony

Interestingly, the tencha-ho method, the prototype of matcha, declined in China, its birthplace, after the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Meanwhile, in Japan, it developed uniquely as tea ceremony culture. During the Muromachi period, a game called “tocha” (tea contest), where participants guessed the origin and quality of tea, became popular among nobles and warriors. Eventually, the spirit of “wabi-cha” (rustic tea) was established by Murata Juko (1423-1502), Takeno Joo (1502-1555), and Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591).

In Japan, tea cultivation methods also evolved. Particularly in Uji, a unique method called “oishita saibai” (shaded cultivation), where tea plants are covered to block sunlight, developed around the 14th century. This resulted in high-quality matcha with increased umami and reduced bitterness. Currently, Shizuoka, Kyoto, Aichi, and Fukuoka are the main matcha-producing regions.

Thus, although matcha originated in China, it evolved uniquely in Japan, becoming a symbol of Japanese culture.

Development of Chinese Tea Culture and Birth of Matcha

Tang Dynasty China and the Origin of Powdered Tea

The history of matcha dates back to Tang Dynasty China (618-907). During this era, a method called “dancha” was mainstream in China. This involved steaming tea leaves, crushing them, placing them in molds to solidify, and then scraping off the necessary amount to powder it before dissolving it in hot water. This is considered the prototype of modern matcha.

“The Classic of Tea” (authored by Lu Yu, around 780), the world’s oldest tea book written during the Tang Dynasty, already describes the method of brewing powdered tea with hot water. This document is highly regarded by tea ceremony researchers as important historical evidence showing the origin of matcha.

Song Dynasty Tea Culture and Development of Matcha

Matcha culture truly blossomed during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). During this period, the “tencha-ho” method of dissolving and frothing powdered tea in hot water was established. Emperor Huizong of Song (1082-1135), known as an enthusiastic tea lover, authored “Daguan Chalun” himself, praising the beauty of green tea in white teabowls.

Notably, the chasen (tea whisk) was invented during this era. The technique of whisking tea with a chasen is almost identical to the method used in modern tea ceremony, making it a traditional technique with over 1,000 years of history.

Decline of Matcha Culture in China

Interestingly, after the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), matcha culture declined in mainland China. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the method of steeping tea leaves, known as “sencha-ho,” became mainstream, and the culture of whisking powdered tea gradually disappeared.

In modern times, the habit of drinking matcha is rarely seen in mainland China. Ironically, matcha culture, born in China, developed and has been preserved in Japan. Japanese tea ceremony, while based on the Song Dynasty’s tencha-ho method, incorporated unique aesthetics and philosophy, elevating it to a globally respected culture.

Zen Monk Eisai and the Path of Matcha’s Introduction to Japan

Zen Master Eisai and the Contributions of “Kissa Yojoki”

The formal beginning of matcha culture in Japan dates back to the early Kamakura period. In 1191, Zen Master Eisai (1141-1215), known as the founder of the Rinzai sect, brought back tea seeds when returning from Song China, marking a turning point in Japan’s matcha culture. Eisai planted tea near Heian-kyo in Kyoto and in Dazaifu, spreading cultivation methods.

Notably, Eisai authored “Kissa Yojoki” (1211), considered Japan’s first book on tea, detailing the benefits and consumption methods of tea. In it, Eisai emphasized tea’s health benefits, stating “Tea is the elixir of health and the art of longevity,” explaining the importance of tea to the warrior and noble classes of the time.

Introduction and Transformation of Song-style Tea Drinking

The tea-drinking method Eisai introduced is called “Song-style tea drinking,” which became the prototype of modern matcha. This method involved grinding tea leaves finely with a stone mill and stirring them into hot water. Interestingly, this method, already declining in China at the time, would undergo unique development in Japan.

Interestingly, Eisai’s main purpose in spreading tea was as part of Buddhist practice. Tea was used to ward off drowsiness during long zazen meditation sessions, and tea culture spread centered around Zen temples. Tea cultivation was actively practiced particularly at temples founded by Eisai, such as Kennin-ji in Kyoto and Kenchō-ji in Kamakura.

Penetration into Warrior Society and the Popularity of “Tocha”

From the 13th to 14th centuries, matcha spread to the warrior class of the Kamakura shogunate. A game called “tocha,” where participants guessed the origin of tea, became popular and developed as a luxurious entertainment where expensive tea leaves were wagered. According to existing historical materials, the Ashikaga shogun family and powerful daimyo lords competed to hold tea gatherings, creating a culture where imported tea from China and high-grade domestic tea were displayed.

In this way, matcha, introduced by Eisai, transformed from a Zen practice method to a cultural preference of warrior society. And until the aesthetic of “wabi-cha” was established by Murata Juko during the later Muromachi period, matcha was refined among Japan’s upper classes and took root as a unique culture.

Matcha Culture Spreading in the Kamakura and Muromachi Periods and the Foundation of Tea Ceremony

The Rise of Matcha Among the Warrior Class

As the Kamakura period (1185-1333) began, matcha culture reached a major turning point. Zen Master Eisai, returning from China, authored “Kissa Yojoki,” spreading the benefits of matcha, which led to the spread of matcha consumption centered around the warrior class. In particular, a ritual called “charei,” linked with Zen practice, developed, forming the foundation of Japan’s unique matcha culture that emphasizes spirituality.

According to research, matcha during this era was popular among warriors and nobles as a game called “tocha,” where participants guessed the origin and quality of tea. According to materials from the National Museum of Japanese History, several tea-producing regions competed during the late Kamakura period, with Uji tea in particular being highly valued as a luxury item.

The Ashikaga Shogun Family and the Development of Tea Ceremony

In the Muromachi period (1336-1573), matcha culture became even more refined. Notably, the third shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and the eighth shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa actively protected tea ceremony and established tea rooms in Kinkaku-ji and Ginkaku-ji temples. During this era, high-quality Chinese tea utensils called “karamono” were treasured and became elements that elevated the formality of tea gatherings.

According to records from the Kyoto Prefectural Archives, in the middle of the Muromachi period, spaces dedicated to tea gatherings called “kaisho” appeared, and the spatial aesthetics of tea ceremony began to develop. Additionally, Murata Juko (1423-1502) advocated the concept of “wabi-cha,” indicating the direction of Japanese-style tea ceremony that values simple and modest beauty.

Establishment of the Spirituality of Tea Ceremony

In the late Muromachi period, Takeno Joo (1502-1555) inherited Juko’s teachings and further deepened the spirit of “wabi.” His disciple, Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), perfected the aesthetics of “wabi-sabi” and established the foundation of today’s tea ceremony.

According to tea ceremony historian Dr. Isao Kumakura, spiritual ideals of tea ceremony such as “ichigo ichie” (once-in-a-lifetime encounter) and “wa-kei-sei-jaku” (harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility) were established during this era, elevating matcha from merely a beverage to a unique cultural and spiritual practice. Matcha became not just a drink but a means to deepen self-cultivation and interaction with others, occupying a central position in Japanese culture.

Sen no Rikyu and the Completion of Wabi-cha—Matcha Becomes the Core of Japanese Culture

Sen no Rikyu’s Innovation and the Spirit of Wabi-cha

At the end of the Sengoku period, Japanese matcha culture reached artistic completion through Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). Rikyu transformed tea ceremony from the gorgeous “karamono-suki” to “wabi-cha,” which pursued simple and modest beauty. The wabi-cha perfected by Rikyu was not just matcha as a beverage but became the core of tea ceremony that continues to this day as a symbol of Japanese aesthetics and spirituality.

The Aesthetics of “Wabi-Sabi” and Matcha

Rikyu’s tea ceremony is based on the aesthetics of “wabi-sabi.” A simple and modest tea room, tea utensils that utilize natural materials, and the spirit of “ichigo ichie” (once-in-a-lifetime encounter)—these express uniquely Japanese aesthetics. The tea room “Tai-an” is only about two tatami mats in size, yet harbors deep beauty in its simplicity. Rikyu said, “Tea ceremony is merely boiling water, preparing tea, and drinking it,” but within this seemingly simple act is condensed the profound aesthetics of Japanese culture.

The Connection Between Politics and Tea

Rikyu served as the tea master for the highest powers of the time, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and tea ceremony transcended mere cultural activity to take on political significance. “Tea gatherings” became venues for informal meetings among military commanders, and sometimes important political decisions were made in tea rooms. This phenomenon, called “tea ceremony politics,” shows how deeply matcha culture was rooted in Japanese history.

Rikyu’s Legacy and Influence on Modern Times

After Rikyu’s death, his tea ceremony was inherited by various schools, including the three Senke schools (Omote Senke, Ura Senke, and Mushanokoji Senke), and continues to this day. In modern Japan, tea ceremony is not just a traditional culture but is enjoyed by many people as a path of spiritual cultivation. Matcha itself is widely enjoyed as an ingredient in Japanese sweets and desserts, and in recent years has attracted global attention as a health food.

The spirit of wabi-cha perfected by Rikyu, finding true richness in simplicity, speaks to us as the essence of Japanese culture, transcending over 400 years. Matcha has transcended being just a beverage to become a mirror reflecting Japanese aesthetics, philosophy, and way of life itself.

ピックアップ記事

Comments