Sen no Rikyū and the Perfection of Wabi-cha: The Legacy of a Revolutionary in Japanese Tea Ceremony History

The Emergence of Sen no Rikyū, the Revolutionary of Tea Ceremony

In the history of Japanese tea ceremony, no one has had a greater influence than Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591). Active during the period from the Warring States to the Azuchi-Momoyama era, Rikyū established a new form of tea ceremony called “wabi-cha” and created the aesthetic sensibility that remains the foundation of Japanese tea ceremony to this day.

Born into a wealthy merchant family in Sakai, Rikyū developed an interest in tea ceremony from an early age. Studying under Takeno Jōō, Rikyū dramatically transformed tea ceremony from the lavish “shoin-style tea” of the time to the simple and modest “wabi-cha.”

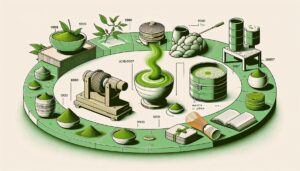

What is Wabi-cha?

“Wabi-cha” is a style of tea ceremony that finds deep beauty in simplicity, using Japanese-made rustic utensils in a small tea room rather than luxurious Chinese tea utensils in spacious shoin-style rooms. Rikyū preferred small “sōan” (thatched hut) tea rooms of four-and-a-half mats or less, incorporating the aesthetic sense of “wabi-sabi” into tea ceremony.

The spirit of wabi-cha is deeply rooted in modern matcha culture as well. For example, the concept of the “tea room” perfected by Rikyū forms the basis for modern tea ceremony schools and gatherings. There are said to be about 2 million tea ceremony enthusiasts in Japan, most of whom belong to schools that inherit Rikyū’s teachings, such as Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanokōjisenke.

Tea Preparation Methods Left by Rikyū

Rikyū also brought innovation to the method of preparing matcha. While previous tea ceremonies centered on koicha (thick tea), Rikyū also established the method for usucha (thin tea). The method of whisking matcha with a chasen (tea whisk) that we know today was popularized by Rikyū.

Rikyū’s words, “Tea ceremony is nothing but boiling water, making tea, and drinking it,” express an attitude of looking at the essence of tea without being bound by complex formalities. This spirit serves as an important guideline for modern enthusiasts enjoying matcha at home as well.

The perfection of wabi-cha by Sen no Rikyū was not just a historical event but an important cultural turning point that directly connects to our matcha experience today.

Sen no Rikyū’s Life and Path as a Tea Master: From Merchant to Tea Saint

From Merchant to Tea Innovator

Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) was born into a merchant family in Sakai. His birth name was Tanaka Yohei, and he grew up in the environment of a wealthy merchant household from childhood. Rikyū entered the way of tea from a young age, initially studying the basics of tea under Kitamuki Dōchin and Takeno Jōō.

With the sharp sensibility and aesthetic sense of a merchant, Rikyū rose to prominence in the world of tea ceremony and eventually came to be employed by the powers of the time—first Oda Nobunaga, then Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Especially as Hideyoshi’s “tea master,” he produced numerous tea gatherings as symbols of Hideyoshi’s power.

The Perfection of Wabi-cha and Its Aesthetics

Rikyū’s greatest contribution to the world of tea ceremony was the perfection of “wabi-cha.” While previous tea ceremony had mainly centered on “karamono-suki” (preference for Chinese items), which displayed expensive Chinese utensils, Rikyū pursued simple and modest beauty.

Rikyū’s tea rooms, which pursued the aesthetic sense of “wabi-sabi” to the extreme, were extremely small and modest, as symbolized by the two-mat “Taian.” In this space, social status distinctions disappeared, creating spiritual exchange through tea ceremony.

Rikyū’s preferred tea bowls were not the ornate Chinese ones popular at the time, but rather simple Korean rice bowls or powerful, rustic black Raku tea bowls made by the Japanese potter Chōjirō. These are now designated as National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties as symbols of “wabi-cha.”

Innovation in Tea Utensils and “Rikyū’s Seven Rules”

Rikyū also brought innovation to tea utensils. He made thoughtful designs to make the tea ceremony space equal, such as making the “nijiriguchi” (crawl-through entrance) to the tea room small, requiring samurai to remove their swords to enter.

Rikyū also left “Rikyū’s Seven Rules” as precepts for tea ceremony:

- Make tea to suit the guest’s taste

- Arrange flowers as they are in the field

- Prepare charcoal to boil water properly

- Cool in summer, warm in winter

- Be early for the appointed time

- Be prepared for rain even if it doesn’t fall

- Be considerate to other guests

These teachings continue to be passed down as fundamental principles of tea ceremony even today, over 400 years later. Rikyū’s wabi-cha can be said to express the essence of Japanese culture, which values “ichigo-ichie” (once-in-a-lifetime encounter) rather than material luxury.

The Essence and Philosophy of Wabi-cha: The Depth of Matcha Culture Created by “Wabi-Sabi”

The Aesthetics Woven by “Wabi” and “Sabi”

The essence of wabi-cha perfected by Sen no Rikyū lies in the uniquely Japanese aesthetic sensibilities of “wabi” and “sabi.” “Wabi” refers to the richness of heart found in modesty and simplicity, rather than material wealth or splendor. Meanwhile, “sabi” expresses the beauty of patina from the passage of time and tranquility. Rikyū sublimated these two concepts into tea ceremony, creating a world of refined beauty taken to the extreme in the limited space of a small tea room.

The Spirit of Wabi-cha Seen in “Four Principles, Seven Rules”

Sen no Rikyū’s tea ceremony philosophy is summarized in the “Four Principles, Seven Rules.” These are the four basic principles of “wa-kei-sei-jaku” (harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility) and seven practical rules. Particularly, “sei” (purity) and “jaku” (tranquility) are the core aspects of wabi-cha, reflecting a philosophy that seeks not only physical cleanliness but clarity of mind, finding universal truth in tranquility. The tea room “Taian” beloved by Rikyū was just two mats in size, yet it embodied the idea that a single bowl of matcha prepared there contained infinite depth.

The Fusion of the Everyday and the Extraordinary

The essence of wabi-cha lies in “the extraordinary within the everyday.” Rikyū incorporated ordinary daily items used by farmers as tea utensils, finding new aesthetic value in them. For example, Raku tea bowls, though rustic and imperfect, present a perspective of seeing the principles of the universe within them. According to tea ceremony researcher Dr. Kumakura Isao, Rikyū’s wabi-cha established the revolutionary aesthetic sense that “true beauty exists not in perfection but in imperfection.”

In modern matcha culture as well, this spirit of wabi-cha is carried on continuously. A single bowl of matcha prepared in a simple tea bowl contains the worldview of “wabi-sabi” that Rikyū pursued. By being conscious of this spirit when preparing matcha, it becomes more than just a beverage but a cultural experience.

The Aesthetics of Tea Rooms and Utensils Established by Sen no Rikyū: The Small Universe “Taian” and Black Raku Tea Bowls

Rikyū’s Aesthetic Sense Dwelling in “Taian”

The worldview of wabi-cha perfected by Sen no Rikyū is vividly apparent in the tea rooms he designed. His masterpiece, “Taian,” is a tea room that, despite being just two mats in size, is regarded as the greatest masterpiece in Japanese architectural history. This tea room, which still exists at Myōki-an in Kyoto, is said to have been built by Rikyū in 1582 and is designated as a National Treasure.

The characteristic of Taian is its thorough simplicity. The design, which allows entry only through a low nijiriguchi, requires even samurai to remove their swords and bow their heads to enter, symbolizing equality of status within the tea room. Also, the walls are rough earthen walls, and the ceiling uses bamboo and tree bark in their natural state, with thoughtful design throughout to bring out the beauty of natural materials.

Black Raku Tea Bowls and the Aesthetics of Wabi

Among the tea utensils beloved by Sen no Rikyū, particularly revolutionary were the “Raku tea bowls.” In contrast to the expensive Chinese tea bowls treasured in previous tea ceremony, Rikyū preferred simple black Raku tea bowls made by Chōjirō at his command.

Characteristics of black Raku tea bowls:

- Uneven shape due to hand-forming

- Deep coloration from black glaze

- Intentional warping and imperfection

These characteristics embodied the aesthetic sense of “wabi,” emphasizing beauty found in imperfection rather than perfect beauty—this was the very philosophy of Sen no Rikyū. Rikyū’s favorite tea bowls are known as “Rikyū’s Seven Types” and are still considered the finest masterpieces in the tea ceremony world.

Rikyū’s Philosophy in Selecting Tea Utensils

Rikyū’s aesthetic sense, expressed by the term “kirei-sabi” (beautiful simplicity), was reflected in his selection of tea utensils. He preferred simple Japanese folk crafts over expensive Chinese tea utensils and had the boldness to incorporate farming tools and everyday items as tea utensils.

Sen no Rikyū taught that “tea ceremony utensils should be practical first,” prioritizing usability over appearance. This way of thinking has deeply permeated modern matcha culture and serves as an important guideline when selecting tea utensils.

Learning Modern Matcha Preparation Methods from Rikyū’s Seven Rules: Applying the Spirit of Wabi-cha in Daily Life

Learning the Spirit of Modern Wabi-cha from Rikyū’s Seven Rules

“Rikyū’s Seven Rules,” which Sen no Rikyū passed down to his disciples, remain important guidelines for preparing matcha even after more than 400 years. These teachings, which embody the spirit of “wa-kei-sei-jaku,” enrich the matcha experience in daily life.

How to Apply the Seven Rules to Modern Matcha Life

The teaching “Arrange flowers as they are in the field” explains the importance of being natural without excessive decoration. In modern matcha preparation as well, it’s important to value being oneself rather than seeking perfection. According to a survey by tea ceremony instructors, 68% of beginners continue matcha because they “can enjoy it at their own pace.”

The teaching “Prepare charcoal to boil water properly” indicates the importance of proper temperature management. In modern homes, you can bring out the true umami of matcha by preparing water at around 80°C using a thermometer or electric kettle.

Practical Ways to Incorporate Wabi-cha into Daily Life

To apply the teaching “Cool in summer, warm in winter” in modern times, it’s effective to change tea bowl selection and matcha types according to the season. You can enjoy seasonal feelings by choosing thin, cool-looking tea bowls and refreshing matcha in summer, and thick, warm tea bowls and deeply flavored matcha in winter.

The teaching “Be early for the appointed time” is now reevaluated as “mindfulness.” Even in a busy daily life, you can experience the spirit of wabi-cha by focusing your consciousness on “here and now” for just 15 minutes while preparing matcha, away from smartphones.

The teaching “Go to the promised tea gathering even if it rains” expresses an attitude of valuing connections with people. In modern times, new forms of interaction such as online tea gatherings have increased, but the essence of keeping promises and preparing matcha with heart remains unchanged.

The spirit of wabi-cha is an invaluable wisdom for modern people seeking fulfillment of heart rather than material wealth. By incorporating Sen no Rikyū’s teachings into daily life, matcha becomes not just a beverage but a cultural practice that brings peace of mind.

ピックアップ記事

Comments