In the elegant imperial court of the Heian period, where royalty and aristocrats gathered, a culture was quietly blooming. This was the “matcha culture” that would become the origin of Japanese tea ceremony. The history of the matcha we enjoy today dates back more than 1,000 years.

The Introduction of Tea and Its Encounter with Heian Aristocrats

During the Heian period (794-1185), tea brought from China gradually spread among Japan’s upper classes. According to historical materials, tea seeds brought back by Saicho and Kukai, who were envoys to the Tang Dynasty, are considered the beginning of tea cultivation in Japan. Particularly, in the early 9th century, a record in “Nihon Koki” states that Emperor Saga drank tea cultivated in Omi (present-day Shiga Prefecture), which is considered the first official record of tea in Japan.

For the aristocrats of that time, tea was not just a beverage but a symbol of Chinese culture and a refined taste. They enjoyed tea in the “Kara-yo” style, a Chinese manner, savoring its aroma and taste.

Tea as Medicine and an Aristocratic Pastime

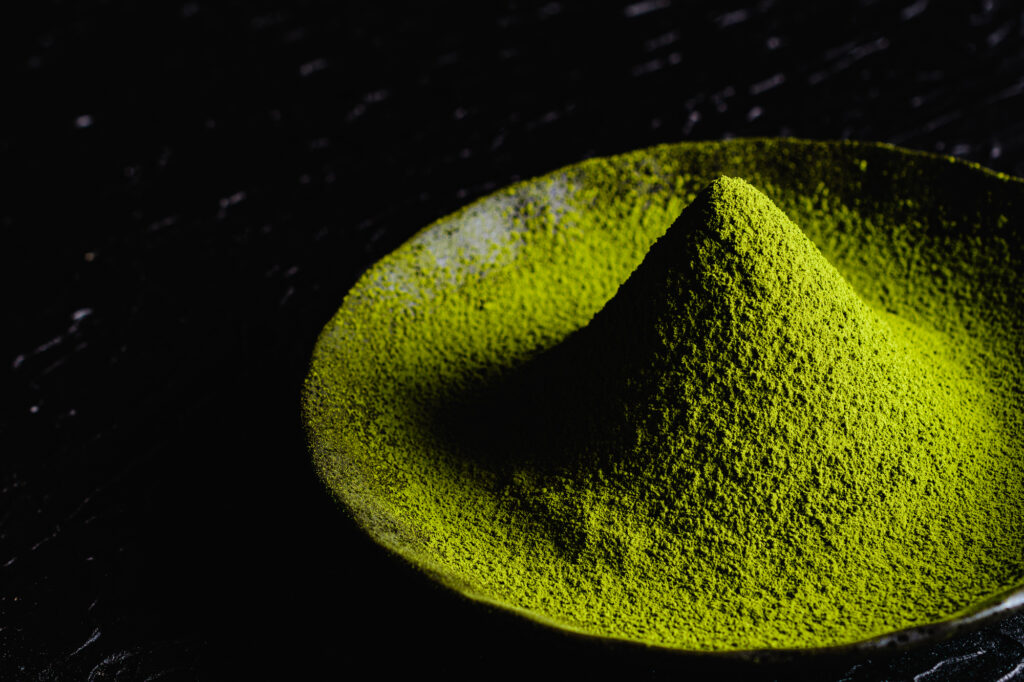

Matcha in the Heian period differed in production method from modern matcha; it was made by steaming tea leaves, drying them, and then grinding them into powder with a mortar. During this era, tea was primarily valued as medicine. “Honzo Wamyo” (circa 918) lists tea as a medicine, noting its detoxifying and awakening effects.

Among aristocrats, tea drinking gradually developed into a cultural activity. Tea references can be found in Heian literature such as “The Tale of Genji” and “The Pillow Book,” and tea was sometimes served at cultural events like poetry competitions and poetry gatherings.

Characteristics of Heian Tea Ceremony and Its Influence on Modern Times

There were two ways of drinking tea in the Heian period: “sencha-ho,” which involved brewing tea leaves, and “tencha-ho,” which involved dissolving powdered tea in hot water. The latter became the prototype for matcha culture that would develop in the Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

Archaeological excavations have unearthed high-quality Chinese tea bowls from late Heian period aristocratic residences, suggesting that there was already a discernment for tea utensils at that time. According to a survey by the National Museum of Japanese History, about 40% of tea utensils excavated from 12th-century Heian-kyo ruins were imported items.

The matcha culture that sprouted in the Heian period later developed under the influence of Zen Buddhism and eventually evolved into a unique Japanese tea ceremony bound with the aesthetic of “wabi-cha.” The refined sensibility of Heian aristocrats continues to pulse at the core of the spirituality and aesthetics of the tea ceremony we enjoy today.

The Role of Tea in Heian Aristocratic Life and Its Cultural Background

Tea Ceremonies in the Daily Lives of Aristocrats

In Heian period (794-1185) aristocratic society, tea was not merely a beverage but a refined cultural symbol. Tea at that time, different from modern matcha, was mainly imported from China as solid “dancha” (cake tea) and treated as a valuable commodity. Tea references can be found in Heian literature such as “The Pillow Book” and “The Tale of Genji,” indicating it was especially prized among the upper classes.

The aristocrats held tea appreciation gatherings called “tocha,” enjoying games to guess the origin and quality of tea. This was not just entertainment but also a social occasion to demonstrate cultivation and aesthetic judgment. For Heian aristocrats, tea represented an expression of cultural identity that fused admiration for Chinese culture with Japanese refinement.

The Connection Between Buddhist Rituals and Tea

A distinctive feature of Heian period tea culture was its strong connection to Buddhism. Saicho and Kukai are said to have brought back tea seeds from China in the 9th century, and tea cultivation spread particularly around temples. Uji and Togano-o became known as famous tea-producing regions early on.

Tea was valuable in Buddhist practice and rituals as a beverage with awakening effects. A ritual called “charei,” offering tea before Buddha, was also performed, which greatly influenced the spirituality of later tea ceremony. According to “Ruiju Kokushi,” there is a record of Emperor Saga drinking tea with monks at Senyu-ji temple, indicating that tea was an important medium connecting the imperial family, aristocrats, and Buddhism.

Among aristocrats, tea was not just to be tasted but also to be appreciated for its aroma, color, and the beauty of tea utensils. Expensive tea utensils imported from China functioned as important status symbols demonstrating the wealth and cultivation of aristocrats, becoming tied to the uniquely Heian aesthetic sensibility of “mono no aware.”

Tea Culture Transmitted from China and Its Transformation in the Heian Period

Tea Culture from the Tang Dynasty

The matcha culture that permeated Heian aristocratic society was actually an imported culture from China. From the late 8th to early 9th century, tea seeds and production methods were brought to Japan from Tang (present-day China) by envoys. Particularly during Emperor Saga’s reign (809-823), historical materials such as “Nihon Koki” record that Saicho and Kukai brought back tea seeds from Tang and began cultivation on Mt. Hiei and Mt. Koya.

Initial Chinese tea differed from modern matcha and was in a form called “dancha.” This involved steaming tea leaves, compressing them, drying them, and then shaping them into discs or cakes. The main method was to break off pieces as needed and brew them.

How Heian Aristocrats Enjoyed Tea

By the middle of the Heian period, tea had established itself as a luxury item among aristocrats. In “The Pillow Book,” Sei Shonagon lists tea as something “okashiki” (interesting or delightful), indicating that tea was a daily beverage for the upper class of the time.

What’s interesting is how tea was drunk during the Heian period. Rather than whisking it like modern matcha, the following methods were common:

- Sencha-ho: Breaking up dancha and brewing it in hot water

- Sancha-ho: Powdering tea leaves, putting them in hot water, and flavoring with salt or ginger

- Cha-gayu: Cooking rice with tea

Especially among aristocrats, a game called “tocha” to guess the origin and quality of tea began to be played, and a culture of tea appreciation was beginning to emerge.

In the late Heian period, a new tea culture was introduced from Song China. This became the prototype of matcha that would be spread by Eisai in the later Kamakura period and develop into Japan’s unique tea ceremony culture. The Heian period was an important era when Japanese tea culture was received from China and began to undergo Japanese transformation.

Ancient Matcha Etiquette Loved in Aristocratic Banquets and Ceremonies

Tea’s Role in Imperial Court Ceremonies

In Heian aristocratic society, matcha (then simply called “tea”) was not just a beverage but an essential element of important ceremonies and banquets. Particularly in official court events, serving tea was established as part of the ritual. Ancient records such as “Ko-yuki” and “Midō Kanpaku Ki” note that tea was served at important ceremonies attended by the emperor and high-ranking aristocrats.

On these occasions, the medicinal properties of tea were also valued. The aristocrats of the time believed, based on knowledge of “herbology” transmitted from China, that tea had effects to “purify the spirit, ward off drowsiness, and lighten the heart.”

The Beginning of Aristocratic Tea Gatherings and Etiquette

By the middle of the Heian period, private tea gatherings began to be held among aristocrats. This was a cultural activity that could be called the prototype of later tea ceremony. In the residences of powerful figures like Fujiwara no Michinaga and Fujiwara no Yorimichi, tea gatherings using rare tea utensils from China were held, and a refined sensibility regarding how to savor tea and its etiquette was nurtured among participants.

The way of brewing tea at that time differed from modern matcha; powder ground from tea leaves in a mortar was dissolved in hot water, sometimes with spices like salt or ginger added. In “The Pillow Book,” Sei Shonagon writes about behavior at tea gatherings as something “okashiki” (interesting or delightful), indicating that tea etiquette was already valued as part of aristocratic cultivation.

Development of Tea Utensils and Aesthetic Sensibility

What is particularly noteworthy in Heian aristocratic tea culture was the high aesthetic sensibility toward tea utensils. High-quality tea bowls and tea containers imported from China were treated as the finest furnishings of the time. Especially Tenmoku tea bowls from the Song Dynasty captivated aristocrats with their black glaze and unique patterns.

The place for preparing tea was also considered important, and a dedicated space called a “charyo” was sometimes established in a corner of shinden-zukuri mansions. Here, a culture of enjoying tea with all five senses was nurtured, decorating with seasonal flowers and using elegant utensils. This refined matcha culture of Heian aristocrats became the foundation of Japanese tea ceremony that continues to the present day, after passing through the Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

Tea Scenes Depicted in Heian Literature and Aristocratic Pastimes

The World of Tea in Literature

The presence of tea in aristocratic life is depicted throughout Heian literature. Representative works such as “The Tale of Genji” and “The Pillow Book” delicately describe tea hospitality at court and scenes of aristocrats enjoying tea. Particularly in “The Pillow Book,” Sei Shonagon lists “the sound of brewing tea” as something “okashiki” (interesting or delightful), suggesting that tea had already established itself as a daily culture at that time.

Tea Scenes in Waka Poetry

Expressions related to tea can also be found in Heian period waka poetry collections. For example, in “Kokin Wakashu,” there is the poem:

“In the mountain village, winter’s loneliness is deepened, thinking that neither human eyes nor grass remains.”

Tea practitioners have valued this poem as something that resonates with the spirit of wabi-sabi in the tea ceremony. Even waka that don’t directly mention tea but express harmony with nature or the beauty of tranquility greatly influenced the aesthetic sensibility of later tea ceremony.

Tea as Aristocratic Cultivation

From the middle of the Heian period onward, tea transcended being just a beverage to become a cultural activity expressing aristocratic cultivation and aesthetic sensibility. Particularly, powerful figures such as Fujiwara no Michinaga and Fujiwara no Yorimichi hosted tea gatherings and demonstrated their cultural refinement and authority by serving tea using high-grade tea leaves from China.

“Eiga Monogatari” describes how Michinaga prepared tea using utensils imported from China to entertain guests, indicating that tea had become an important element of socializing in aristocratic society.

Thus, tea scenes depicted in Heian literature not only convey the living culture of the time but are also deeply involved in the formation of Japanese aesthetic sensibility and spirituality. The tea culture nurtured by Heian aristocrats formed an important foundation that would develop into wabi-sabi tea ceremony through the later Kamakura and Muromachi periods. In understanding modern matcha culture, knowing the position of tea in Heian aristocratic society has great significance in feeling the continuity and depth of Japanese culture.

ピックアップ記事

Comments